CNBC.com

October 30, 2018

By: Megan Leonhardt

Click here to link to the original article at CNBC.com

United Airlines failed to address critical food safety issues at Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey, endangered passengers and retaliated against employees for speaking up, three high-level managers who worked in its catering division allege in lawsuits filed last month.

United Airlines did not address persistent maintenance issues at its catering facility at Newark airport, which allowed the spread of several strains of the bacteria listeria, including the potentially deadly Listeria monocytogenes, the lawsuits say. Further, once the listeria was discovered, they say, United didn't act aggressively to contain it.

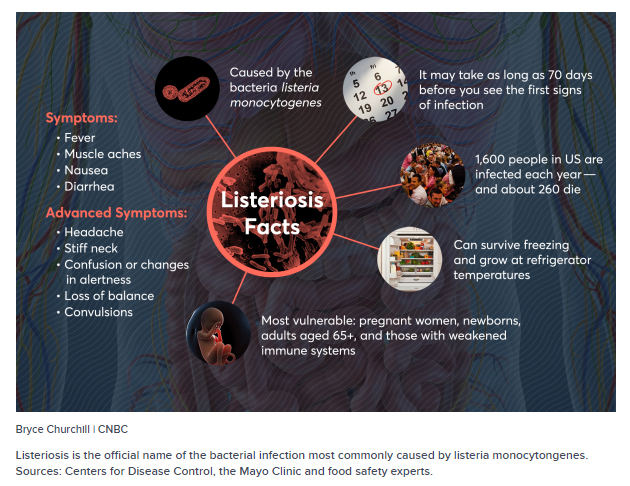

Listeria monocytogenes, or L. mono as it's known, is a particularly nasty strain of bacteria that can cause stillbirths in pregnant women and serious health complications for the elderly and those with immune deficiencies. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that about 1,600 people get sick from L. mono each year, and about 260 die.

Initial symptoms include fever, muscle aches, nausea and diarrhea, according to the Mayo Clinic. Listeria can also invade the central nervous system and cause meningitis, or a blood infection. Because it can have a long incubation period — symptoms can take up to 70 days to show up — it can be difficult for people to pinpoint when and how they got sick and directly link it with a specific cause, according to food safety experts.

United further engaged in a pattern of disregard for food safety and attempted to cover up problems, according to the lawsuits brought by United's former senior manager of food safety, Marcia Lee, General Manager of the Newark catering facility Eliot Mosby, and Newark Food Safety Manager Gustavo Moya. The lawsuits filed by Lee and Moya were moved to federal court in mid-October.

Specifically, Mosby and Moya say in their lawsuits, when they spoke up about the "intolerable conditions" at the Newark catering facility and pushed for resources to address them, they were stripped of their duties, reassigned to far-flung offices or forced to resign.

The lawsuits are seeking damages for lost pay and benefits, as well as compensation for alleged humiliation and mental and emotional distress. Mosby's suit asks for compensatory damages of $7.5 million, and the other two do not specify an amount.

In a statement to CNBC, United denied these allegations and said the lawsuits were without merit. "Everyone at United Airlines, including our leadership, is committed to serving our customers the safest and highest quality food in the air, which is why we have expanded our industry-leading food safety program, added several experts to our food safety team and are investing more than $21 million to enhance our catering facilities."

Additionally, United told CNBC it is unaware of any foodborne illnesses confirmed to be linked to any food served on its flights, and is currently cleaning and repairing several areas of the Newark facility as part of routine maintenance.

This is not the first time United has had to cope with reports of listeria at its food-production facilities. In November 2017, the USDA announced a recall of some chicken and pork products produced at United's Denver catering operation after the facility notified regulators that one of its products had tested positive for L. mono. Local news outlets reported that listeria contamination halted production at the facility.

In August 2018, a local New Jersey news station reported that United had found listeria at its Newark location as well. At the time, United said it found listeria in its cooler but noted listeria had not been found in food served to its customers or on food-contact surfaces. Further, it said the cooler had been cleaned and the bacteria contained.

The suits claim United's issues with listeria, and food safety generally, are much bigger and broader reaching than previously reported.

Listeria found at Newark

United has in-house catering facilities in Cleveland, Denver, Honolulu, Houston and Newark that employ 2,700 workers to cook and assemble roughly 100,000 meals daily, according to the airline. Some of the meal components consist of prepackaged items from outside vendors, but many of the dishes are made in-house.

The Newark operation, which does business as Chelsea Food Services, is the airline's largest. It supplies up to 45,000 meals a day to both domestic and international flights, United confirmed to CNBC.

In her lawsuit, Lee says the food at the Newark catering facility tested positive for listeria starting in September 2017. (The lawsuit did not specify which type of listeria was found; some strains are innocuous.) Following the positive result, Lee claims she informed United it would have to put the entire lot of potentially tainted food products on hold, but airline management refused.

"United's upper management resisted keeping the food on hold due to business concerns, and advised [Lee], in sum and substance, that United was going to delay making mandatory reports to the FDA concerning the situation," the lawsuit says.

United told CNBC it was listeria innocua in September 2017, which is generally not harmful to humans, and said it disposed of the food. The airline says it stopped testing food for pathogens like listeria in December 2017. It tests the environment the food is made in rather than the food itself, which satisfies legal requirements. United says it prefers this procedure so that food doesn't sit around for 72 hours.

In his suit, Mosby says in 2017 he began sounding the alarm about the overall condition of Newark's largest food production room, a 7,500-square-foot work area that United refers to as "Cooler 7," which he called "a total disaster" and "major public health risk" due to its "unsafe" refrigeration temperatures that kept food too warm.

In February 2018, internal testing documents provided to CNBC showed positive results on the wall in Cooler 7 for the far more dangerous food pathogen L. mono. A drain and workstation table legs tested positive for listeria as well, although the specific type was not confirmed at that time, according to the testing reports.

From February to mid-August, more than 175 tests performed at Newark came back positive for listeria, 27 of which were classified as L. mono, according to these internal records.

United confirmed to CNBC that it found listeria in the Newark facility between February and August of this year but disputed the extent and the seriousness of the contamination. The airline says it took appropriate actions in line with federal guidelines to contain the listeria, including intensifying its cleaning, retesting the affected areas, and, if they still tested positive, removing the equipment.

Yet food safety experts told CNBC that if there's L. mono in multiple areas of a food production facility, the safest course of action is to shut it down immediately. "You don't really wait when it's that way. Once you find it in the environment, you shut down, you clean up to target listeria, and then you validate to verify that you don't have listeria any longer," says Aurora Saulo, a professor of food safety and an extension specialist in food technology at the University of Hawaii.

"We don't tolerate listeria because it's a very mean microorganism," she adds.

Even though the FDA does not require it, United also should have been testing the food as a matter of practice, food safety expert Melvin Kramer of the EHA Consulting Group, tells CNBC. "The fact that product testing isn't required by United Airlines, I find amazing," Kramer says. "When you have all of these red flags, I think it's very imprudent not to do that."

In mid-August, six months after the first tests revealed L. mono in Cooler 7, Newark manager Mosby shut down the cooler himself, according to his lawsuit. It had become clear, the lawsuit says, that United's upper management was "not going to take the required actions to remediate the food safety problems."

United told CNBC that "management was in agreement about steps to be taken to address issues concerning Cooler 7," including shutting down the area in order to implement an FDA-compliant remediation plan.

A few days after the cooler was taken off line, United reassigned Mosby to its Chicago headquarters where he was given "make-work assignments" to keep him busy and doesn't have a permanent desk, according to his lawsuit.

Health inspectors cite United for 'critical' violations

Lee, Mosby and Moya say the listeria spread could have been avoided.

Listeria is a naturally occurring bacteria, and it's not uncommon for food production facilities to find it occasionally. But regular maintenance and upkeep are crucial to keeping this bacteria controlled and out of food. Cracked floors and broken equipment are ideal breeding grounds for bacteria because they can be difficult to sanitize.

"If you've got cracks in the floor, peeling paint, rust, build-up of gunge, holes, then those are the places that listeria like to hide. So a maintenance program is an important part of controlling risks," says one food safety expert who didn't want to be named because he works with clients like United.

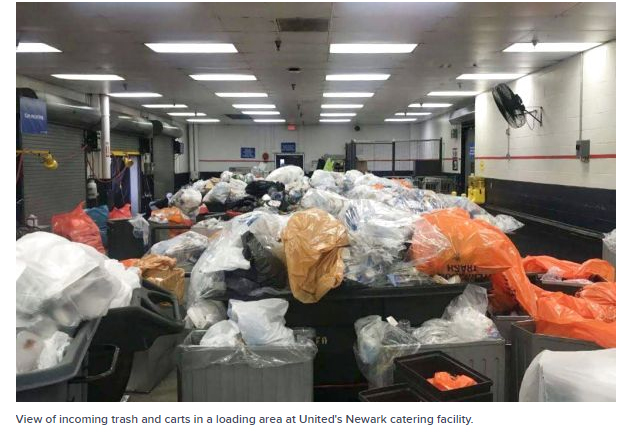

United's Newark catering facility suffered from deferred maintenance, according to the Mosby and Moya lawsuits. "United had intolerable conditions with several of its coolers and collapsed drains which constituted major public health and safety risks," Moya's lawsuit claims.

Refrigeration, in particular, is crucial in keeping food safe for consumption. Most health codes require food be kept at 40 degrees F or below. But multiple food prep areas at Newark — including a food assembly area called Cooler 5 and the larger Cooler 7, where listeria was found — could not maintain proper food temperatures, regularly registering 55 to 60 degrees, according to the Mosby and Moya lawsuits.

A routine inspection on Aug. 24 by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which was referenced in Moya's lawsuit and obtained by CNBC through a Freedom of Information Act, found 11 critical and 34 general violations within the Newark facility.

"I'm never worried about the number of violations; I'm worried about the quality of the violations," Kramer tells CNBC. He noted that several of the Newark violations were "serious" in his opinion, including incorrect temperatures for food and condensation found on doors and on food, a situation which he said could lead to listeria. The report also cited several less-critical cleanliness issues such as flies on the walls and ceiling, "black residue" accumulation near a door, food on the floor, and dust and discoloration on the ceiling tiles.

The report noted a re-inspection was required to ensure the citations were addressed and corrected. But on Sept. 6, Port Authority health inspectors again cited the facility for one critical violation and 13 general violations, including improper food temperatures and condensation issues, according to the re-inspection report obtained via FOIA. Health inspectors ordered another re-inspection.

United acknowledged that not all problems cited by Port Authority were resolved during the Sept. 6 inspection because the company was working off an action plan that required more time to complete. The airline told CNBC that it had since corrected all outstanding violations. The Port Authority declined to comment.

Employees punished for trying to do the right thing, lawsuits claim

All three lawsuits claim employees repeatedly reported verbally and through emails a number of critical food safety violations to United Airlines but United failed to act on them.

Moya filed a complaint with the FDA in July 2018 regarding the food safety violations he says he witnessed at Newark, according to his lawsuit. The FDA confirmed it received at least one complaint about conditions at United's Newark facility.

Moya also sent an email in early August directly to United's executive team, including President Scott Kirby, according to the lawsuit. Moya says his email outlined Newark's "critical food safety violations" and disclosed that he had filed a complaint with the FDA.

All three employees claim that, instead of fixing the problems, United carried out a campaign of unlawful retaliation against them.

"Rather than acknowledge that … numerous disclosures and concerns should have been addressed earlier, and that the listeria outbreak could have been avoided if plaintiff's recommendations and disclosures were heeded, defendants decided to retaliate," Mosby's lawsuit states.

Lee says she was forced to resign in September 2017 after she refused to "participate in serious criminal and/or civil wrongdoing," according to her lawsuit. Mosby was transferred to Chicago following his alleged closure of Cooler 7, and Moya was relieved of his duties at the end of August and also reassigned to the Chicago office, according to their suits.

All three complaints also allege United discriminated against them on the basis of race, sexual orientation and/or religious beliefs.

United told CNBC it disagreed with the retaliation and discrimination claims described in the complaints, and said the company does not tolerate discrimination or retaliation of any kind.

Waiting for their day in court

United told CNBC that while it has never completely shut down the entire Newark catering facility, it is working to fix the bigger problems cited by health inspectors and the known issues with its coolers.

Those projects include an overhaul of Cooler 7, making structural modifications to the ceiling, floors and walls to make its design more hygienic, United said. The airline is also performing updates and repairs to another 5,000-square-foot processing area, Cooler 5, and to drainage in the dish room. It expects to wrap up construction by the end of the month.

United said an FDA inspection last week found no issues. The FDA said it could not confirm or deny the inspection.

Meanwhile, the lawsuits are pending. The suits filed by Lee and Moya are currently in federal court, and United is required to respond by the end of October. Mosby's lawsuit remains in New Jersey state court.